|

The

Importance of Whitehead for Contemporary Theology Donna Bowman March 3, 2005 Thank you so much for the chance to speak to you today. It

is a dream come true, and a humbling experience, to address this audience on

the subject of Whitehead and theology. Let me state my thesis immediately.

Whitehead is important for contemporary theology because Whitehead offers us

a metaphysics of contingency. To explain what I mean by contingency, and why a

metaphysics of contingency is crucial for the survival of theology, I’ll need

to offer a few generalizations about fairly recent history. We’re all familiar with the crisis of liberal theology in

the twentieth century. The 1917 influenza epidemic, World War I, the rise of

fascism, and the Holocaust, serially and collectively undermined the

nineteenth century’s postmillennial faith. This sea change in the fortunes of

Christian theology coincided with dramatic developments in other disciplines.

Idealist philosophy was being pushed aside by existentialism, with its

adamant refusal to speculate about ultimate meanings. At the same time, the

humanities were all being transformed by the rise of the historical

consciousness. With the recognition that we are trapped in the curve of time

and shaped in all our facets by the accident of our location in time and

space, came the abandonment of progressive and hierarchical notions in all

realms of culture. And finally, postmodern thought’s first stirrings

synthesized these new views by calling for the end of appeals to

metanarratives. During this twentieth century revolution, during the

decline and fall of modernism, theology was summarily pushed to the sidelines

of intellectual life. We are all aware of the giants and heroic thinkers who

advanced theology in the twentieth century, including the founders of the

process movement. But the centrality of theology to the academy, to culture,

and to the life of the mind was nevertheless gone, seemingly for good. We

might be tempted to attribute this decline in theology’s fortunes entirely to

the ascendancy of secularism or the recognition of religious pluralism. But

at least in part, the marginalization of theology resulted from theology’s

own failure to find a way out of its addiction to essentialism and

abstraction. The perception of theology in the rest of the disciplines

– and to a large extent, the reality as well – was that any nods toward the

new intellectual situation found in twentieth-century theology were not

central features of theological thinking. Theology was finding it harder than

other disciplines to extricate itself from foundational appeals to necessity,

transcendence, and eternity. How could a way of thinking still dependent in

its mainstream forms on metaphysics, with its claims about what must be true

always, everywhere, and to everyone, possibly remake itself into something

other than a metanarrative – a claim to ultimate, transhistorical truth? Theology did make the linguistic turn along with the rest

of the humanities. It became integrated with the philosophy of language and

recognized itself as a particular kind of speech act, a language game, a

system of meaning dependent on the assent of a particular community. But it

did not make the historical turn as successfully. Theology did not

consistently find a way to speak about God, doctrine, and the life of faith

as fundamentally concrete and contingent realities. When it did move toward

doing so, the speech often turned out to apply specifically to one site, one

location in time and space. Its success was due to its refusal to generalize

or abstract from that single instance to larger universals. However, this

very refusal made it difficult for this thought to be recognizable as

theology. Theology needs to find a way to work with the dominant

systems of thought that assume radical contingency and the absence, or

unavailability, of a transcendent realm either as foundation or authority.

This need is urgent for two reasons. First, the vitality of Christian

theology has always been its ability to make creative use of the best thought

of its time. Theology may never again be central to intellectual life in the

way it was in the premodern or even the modern era. But it will never have

the chance of gaining a hearing in the academy if it is perceived to rely on

the same systems of thought as it did in the days of its ascendancy. Second,

the experience of radical contingency and immanence is central to

twenty-first century lives. A phenomenology of contingent existence could

lead us to a revelation that such a system has depth. Deep contingency can be

a resource for theology, rather than an obstacle to be overcome. Contemporary theology must find a way to celebrate

contingency as such. It must develop methods to see the depths not only in

concrete particulars but in concreteness itself and in particularity itself.

In this address I will argue that Whiteheadian process thought provides such

a method. Whitehead forms a generally applicable system of thought out of

attention to the ultimate reality of individual particulars. If theology can

utilize this framework and model itself after this foundation of

particularity, it will be able to make creative use of contingency as

reality. I’d like to give two examples of the type of contingent

thinking I’m talking about. One illustrates the power of a large-scale,

transcultural view on ideas often taken to be essential. The other reverses

the focus in order to look at the depth and complexity of a single contingent

event. This latter focus, I will suggest, indicates some bias in the way

gender affects one’s perspective on what is ultimately real. Then I want to

explore how Whitehead’s system reveals the connections between particulars

that constitute our experience of contingency. These connections – the

patterns of flow and collection that they create – unite the social and

personal viewpoints on contingent events. My argument is that the

phenomenology of contingency shows us that it is crucial for theology, which

in turn leads us to Whitehead, who provides a metaphysical system that

encompasses and contextualizes contingency itself. My first example comes from Alaskan Inuit culture. Similar

examples can be found in communities elsewhere in the world – In our society, the division of individuals at birth into

binary categories – male and female – is so natural and obvious that most of

us take it entirely for granted. But that taken-for-grantedness itself is a

factor in the hidden existence of millions of people for whom such

categorization is more problematic. In fact, the binary categories do not

simply order themselves, as we so often assume: babies with male genitalia

over here, babies with female genitalia over there. The child pictured here,

for example, does not fall into these categories. We rely on a doctor to make

some definitive determination of sex at birth and record that determination

on a birth certificate. Often, of course, the determination is made even before

birth based on ultrasounds or genetic testing. All the many and varied combinations

of genotype and phenotype are collapsed at that moment into those binary

categories that we live with for the rest of our lives and take for granted

as nature’s categories, too. The need for medical and governmental record-keeping,

therefore, hides the reality that there are millions of intersex individuals

among us. Until recently, doctors and nurses often intervened surgically to

assign a single sex to intersex newborns without parental knowledge or

consent. Now, most often, doctors suggest to parents what sex the child

should be assigned, and what surgery, hormone treatment, or other therapy is

needed to “normalize” the infant. In the Inuit societies studied by Bernard Saladin

d’Anglure, some of the infants are believed to have changed sex at birth –

two-thirds of the time, from boy to girl. Such children are brought up as

girls, and may (or may not) revert to their “biological” sex at puberty. A

mother is believed to determine the sex of her baby during pregnancy, through

dreams. Whatever sex of child is needed to complete a family unit, that is

the sex of the child that is born -regardless of its genitalia.1 In a South

American group with a similarly high incidence of intersex births, sex isn’t

assigned until puberty; children are not designated as boys or girls, but

simply children. What would our society be like if intersexuality were out

in the open – if, like the Inuit, we carried more categories around in our

heads than male and female? Our experience of gender – one of the most

taken-for-granted, intimate, obvious, “natural” experiences we have, one that

we use as an assumption for so many arguments, decisions, and behaviors –

would be completely different. The deep and significant contingency of our

binary view of gender is revealed by contrast with a society that ours could

have been – a society that does not engage in constant categorization for the

purposes of control, as Foucault has described. Recent data suggest that a

different contingent view of gender is on its way; Time magazine reported in 2004 that as many as two percent of

live births in the U.S. exhibit some intersex characteristics, much higher

than anyone has ever thought. As these realities emerge from a cloak of

secrecy, a rethinking of gender is inevitable. The contingency of our practices concerning sex assignment

is only visible from a historical view, or even better, from a transcultural

view such as that afforded by the social sciences. The application of

Cartesian rationalism within our culture is of no avail in distinguishing

between contingencies and necessities here. As Western thought has

demonstrated for centuries, and continues to demonstrate, when we merely

reflect on gender, we can hardly avoid the conclusion that there is something

essential and real about the distinction between male and female. Why doesn’t theology make better use – and more use – of

the data gathered by sociologists of religion? For some time sociology and

anthropology have been the growth areas within the religious studies field.

Yet one can read theological journals for months without coming across any

references to their work. No doubt there are many reasons for this neglect.

But it’s possible that theologians find this data second-rate precisely

because it reflects contingencies – interesting as curiosities, perhaps even

useful for community practice, but not the material for deep theological

reflection. Now I don’t want to misrepresent the state of theology in

the twentieth century. There is no doubt that theology has reflected in a

significant way on historical and cultural contingencies, perhaps most

notably in Paul Tillich’s advocacy and practice of a theology of culture.2

Tillich made use of such diverse cultural forms as the Cold War, the space

program, and psychoanalysis as the raw material for theological work.

However, his view was that religion derives from the human encounter with the

ultimate – with something that both transcends us and puts us in contact with

a particular, privileged point of view. At the same time, religion is a part

of culture. Tillich felt that religion is uniquely placed to uncover the

transcendent source of the greatest works of human culture, a connection to

the ultimate that is revealed in their disproportionate impact and grip on

our imagination. There is an “unconditional” waiting in the phenomenological,

for Tillich. The theology of culture is an uncovering of the transcendence or

ultimate within and behind cultural products. When we engage in a Tillichian theology of culture, then,

we are certainly paying attention to particular concrete cultural moments.

But we are also looking behind or beyond them to a transcendent source. To

someone looking for evidence in theological thought of attention paid to

contingency as such, this move will appear to be an attempt to have it both

ways – to have our historical cake and eat it, too. The twentieth-century

intellectual movements I have described reject any move away from contingency

and toward ultimacy that is too quick, too programmatic, too methodologically

standardized. Those formed by this recognition of radical contingency,

including the entire practice of history and science, will rightly exit

Tillich’s highway as soon as he begins his unveiling. We need, then, another approach to a theology of

contingent particulars. Let me illustrate the material, the matters of fact, for

such a theology through another example.

Recently, reading a moving book by the non-fiction writer

Paul Collins called Not Even Wrong,3

about his son Morgan’s autistic spectrum diagnosis, I came across a passage

which discussed the difficulty autists have taking tests. Test-taking

requires a set of skills that all of us have mastered: the ability to focus

on a series of tasks, one at a time; the ability to move from task to task

without getting hung up or stalled; the ability to concentrate attention on

the test items as a group for a reasonable amount of time without becoming

distracted. All of these abilities are exactly what autists generally lack.

Autists focus intensely on a few preferred activities. Attempts to redirect

them to new activities, especially unfamiliar activities, usually provoke

anger or stubborn refusal. They do not move smoothly in sequence from one

task to another. To focus on a task, for autists, is to be unaware that there

are other tasks waiting to be done. They are unresponsive to instructions

generally, especially if fully engaged in a preferred activity, and are usually

unable to follow multi-step instructions. If engaged in an activity they

don’t particularly favor, they are easily distracted That night I lay awake, wondering if Archer would ever be

able to take a test. Now, there is nothing about test-taking that reaches down

through the layers to the eternal verities. It is completely an artificial

activity, created by humans to meet specific, contingent purposes, namely the

demands of the post-Industrial Revolution societies for standardization,

rank-ordering, tracking, and record-keeping. Prior to 150 years ago, a scant

minority of human beings, even in the West, ever had to take tests. There’s

nothing intrinsically valuable about tests and test-taking skills. They are

worthwhile only because we live in a tiny blip of human history in which they

have been deemed essential, purely for the instrumental purposes of a

peculiar set of institutions (memorably described by Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish).4 So was I worrying about something unreal – or at least

less real than other things truly worthy of my concern? Is the question “will

Archer ever be able to take a test?” worth worrying about? If the answer does

not reach to the level of anything really real, how can it be worth lying

awake for? My husband often has said to me – and I know he means this

sincerely, from the bottom of his heart, and that he believes it – “The only

thing that matters is that Archer is happy.” There is a statement about the

eternal verities, about the absolutely real. Aristotle would whole-heartedly

approve. Test-taking is only important because it is a means to an end –

education and advancement – the final telos

of which can only be happiness. Only happiness is the end that is not a

means to any other end. If Archer can achieve happiness through other means

than test taking and all its accompanying structures, then my worries are not

about reality. They are merely about contingent surface frameworks. Yet my worries are about reality. They are about a reality

as deeply and as fully effective as any universal or any mathematical

abstraction. To a generic male perspective – and here I’ll pick on my

husband, who knows I don’t take offense at his attempts to speak the truth –

contingent surface frameworks, operative only in a particular time, place,

race, social class, et cetera, are troublesome but ultimately ineffectual, if

we can simply will ourselves to see through their fundamentally unreal

nature. Historically speaking, it was felt that if women sometimes insisted

on the reality of the contingent and the contextual, it was because they were

unable to muster up the intellectual energy to extract themselves from the

world of appearances.5 But to me – and I submit, in reality – those

contingent frameworks are not just on the surface. They have depth. They go

all the way down to the base of reality. Just because they are impermanent

and could be otherwise doesn’t mean they aren’t as real as the realest things

there are. Butting my head up against them will give me bruises – not on my body

but in my self -as surely as butting my head up against the reality of a

brick wall. I must take account of them in plotting my future course as

surely as I must take account of God’s eternal purposes, willed since before

the beginning of time. What does Whitehead have to offer in my search for the

truly real? I have already suggested that he is going to support me in my

attempts to find meaning in contingencies. He was certainly concerned with

reality – it’s half of the title of his greatest work. At first glance, the

approach to The Real in Process and Reality appears to be a typical male

“onion-peeling” approach: moving as fast as one can from the world of

appearances to the foundational layers of true actuality, the categories that

apply everywhere, to all entities, at all times. But there are important

differences between the description of reality that emerges from Whitehead’s

method, and the Greek-influenced discovery of the necessary, absolute, and

ultimate that is the culmination of a stereotypical philosophical/theological

search for The Real. For one thing, Whitehead did not discard time as one of

those less real layers that needs to be drilled through to get down to what

is truly real. For another, reality in each new moment is constructed by actual

entities, not solely or even primarily with reference to atemporal eternal

objects, but out of the previous moment’s contingencies. The reality thus

constructed is not a passing, temporary arrangement, but The Real itself,

“brute fact,” “immortal,” as Whitehead puts it,6 gathered into the consequent

nature of God everlastingly. Finally, the aspect of divinity that most aptly

corresponds with the necessary, absolute, and ultimate for which philosophers

have usually searched is the primordial nature of God; yet Whitehead

describes this pole of the divine nature as “deficiently actual.”7 Surely

something “deficiently actual” cannot be “more real” than the actualities

with which we contend on a daily basis. In what remains of this address, I

want to connect the phenomenological description of contingent reality,

especially social reality, to Whitehead’s description of reality in his

philosophy of organism, and make a few comments on how this matters to

theology. I beg your indulgence to allow me to introduce these ideas with

another story. Computer scientists tell the story of Paul Baran, an

engineer with the Rand Corporation in the 1950’s who came up with an idea

while eating a steak dinner.8 He began to ruminate on the components of a

steak dinner: steak, potato, carrots, green beans, buttered bread. This same

list of ingredients, he realized, could have been a stew instead of a steak

dinner. If it had been a stew, the ingredients would have all been mixed

together, and their flavors would have interpenetrated. The meat would have

tasted a little like carrots, and the carrots would have tasted a little like

potatoes. Looking to the right of his plate, he saw a salad, and realized

that this is yet another way the same ingredients could have been used:

tossed together so that the ingredients and flavors remained distinct, but

not segregated.

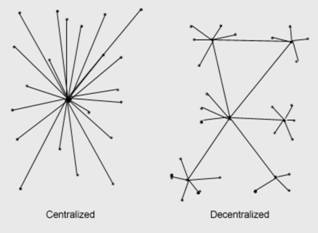

But notice that “steak dinner” reality is merely nominal.

The centralized, hierarchical nature of a steak dinner depends on the concept

of a steak dinner – a concept brought into being by the linguistic creation

of the phrase “steak dinner.” Sure, once that phrase is coined and joined

with a nascent concept of steak, potatoes, et cetera, the reality thus

described is hierarchical. But the hierarchy is dependent on the name “steak

dinner.” Call it “dinner” and the hierarchy disappears. The concept “steak

dinner” is hierarchical, but aside from concrete instantiations of steak

dinners that are created consciously in response to the concept, there is

nothing “real” about the abstraction “steak dinner.” By contrast, we might look at social reality as a

decentralized form of reality – like a stew. It is composed of parts, but the

whole is greater than the sum of the parts. A decentralized network is made

of up several networks that, within the nodes, are arranged hierarchically;

but there is no hierarchy among the networks. Everything penetrates into

everything else, but through a particular point or medium.9 It may seem that Whitehead’s description of reality is

best characterized as decentralized in this way. The idea of interpenetration

of flavors seems to capture the internal relations that constitute entities

in the Whiteheadian system. But this is the case only at the simplest level.

In a stew no hierarchies emerge. But hierarchies do exist in reality. They

are not essential; they are instead temporal, contingent, and relative to a

particular set of circumstances. But they are real. Whitehead says that reality is distributed community –

like a salad. All the ingredients are participating in constituting that

reality (unlike the steak dinner). All the parts are more or less equivalent

(like the stew). There are no status differentials between the objects in the

set at the most basic level. All entities are performing the same function –

the function of constructing reality. And all entities are capable of

performing all the basic functions of the system. However, each entity is

unique, because the position it occupies within the system and the

connections that are made to other entities are unique. (This is the basic

concept behind the Internet: there are no command and control centers, but

there are distinctions between terminals having to do with position in the

network.)

So sets of values and standards – the basis for hierarchy

– emerge not out of the bedrock nature of the distributed reality, but out of

the particular contexts of local nodes of cooperation. The values are only

contextually real, in other words. But on the far side of the node, this is

as real as real can be. Now this description of reality is far truer to my

experience. This is the reality with which I grapple when I lie awake at

night and worry about Archer’s ability to take tests. The test-taking

structures in my social reality – educational and vocational – are concrete

expressions of the values of my node. These structures affect me, and they

will affect Archer. I did not choose the node in which I find myself – but

nevertheless, I am in it. It is my reality. In the node in which I live, I

have no choice but to respond to the values that sit atop this contingent,

unnecessary, but truly real hierarchy. I might choose to ignore the

institutions that administer and interpret tests. I might do my best to label

them illusions and thereby wish them away. I might call this reality “steak

dinner” and talk about the truly real, truly important things at the top of

the reality hierarchy – and test-taking would be far down the pyramid, of no

real importance and therefore deficiently real. Yet despite the fact that the

educational concept governing my reality is just as nominal as “steak

dinner,” the hierarchy of values created by that educational concept is

eminently real. What I mean by “real” here, you will have noticed, is what

Whitehead means by real. To be real is to be efficacious. To be real is to be

important. To be real is to matter. All of these descriptions of reality are

descriptions of worth, of value. And I submit that all descriptions of

reality in fact reduce to descriptions of worth and value. This fact is

betrayed by the way we contrast contingent realities as “not mattering” like

necessary realities. In fact, what we are saying when we say that the

absolute, necessary, and eternal realities are “more real” than other

realities, is that they matter more. This assertion is belied, however, by experiences like my

concern about Archer’s future. Archer’s test-taking skills, or lack thereof,

will matter as much as any other conceivable factor when it comes to his

experiences, opportunities, and interactions with his society. His ability to

achieve happiness through other means may be important on a personal level,

to himself and to those who love him, but it will not matter as much, in

terms of changing the future, as his ability to perform the tasks his society

values. There are some important words elided, of course, when I

say that Archer’s test-taking skills really matter and that they will really

change the future. Perhaps I should add that those skills matter “in the

context of an industrialized society with rigid standardization procedures,”

and that it will change the future that is achievable in that context.

However, such an elision is also taking place when my husband talks about

Archer’s happiness as what really matters. Perhaps he should add that

happiness matters “in a limited, personal sense related to freedom from

suffering or anguish.” The value of happiness, or of the lack of suffering,

is important, and its achievement or embodiment is efficacious for

individuals and their close social circles. But nearly every context that I

can imagine values other things than happiness, and not simply as means to

achieve happiness. Those other things are valued because they are efficacious

in changing the future for individuals and intimate communities like the

family, as well as the larger and more diffuse communities to which everyone

in a node is expected to belong. Allow me to continue to draw out a few more implications

of this model in connection with Whitehead’s description of reality. What my

husband is saying when he says that Archer’s test-taking abilities (or lack

thereof) don’t really matter, is that if I understand reality correctly, the

standards of my community that place great value on tests won’t be able to

hurt me. Like Neo in The Matrix,

through the power of my mental grasp on reality, I will be able to stop the

bullets fired at me by this ultimately illusory construct. If the brick wall

is an illusion, and I run into it, it won’t hurt (as long as my brain doesn’t

expect it to hurt so powerfully that it creates pain impulses out of thin

air). I contend, on the other hand, that the social constructs that surround

me have a visceral reality. When I bump up against them, they hurt – and not

simply because I have been conditioned to think that they will hurt. The

visceral, quasi-physical nature of these constructs arises from the fact that

they are instantiated in a particular physical location – a physical location

that I happen to share. My location limits and influences the values with

which I come into contact, the values I must adopt or somehow respond to

because they mediate the world for me (on this side of the node). Further, my

location within the node limits and influences the chances I have to affect

this hierarchy of values. For Whitehead, the uniqueness of each non-divine actual

entity consists of the physical location of that entity in space-time and the

intersections of feeling created by that location. God’s uniqueness, on the

other hand, is that God has no physical location. So the limitations of my

location in a hierarchy of values I didn’t choose do not apply to God; God is

not limited in that way. God is proximate to every entity, in or out of nodal

hierarchies. But God’s lack of physical location constitutes a different kind

of limitation. My social framework, being physically located, surrounds me

with concrete manifestations of its values, creating a physical matrix

suffused with a hierarchy of importance and therefore of reality. It

configures space and time in a number of physical ways: through architecture,

transportation networks, timetables, and institutional infrastructure. God,

not being physically located, cannot surround me with concrete manifestations

of what God values. Nevertheless, the reality of a social value framework is

not reducible to its physical manifestations – the physical constructions

that surround me. The visceral reality is not equivalent to the physical

reality. The visceral reality, the reality I feel and experience, is mediated

by social systems of value – by the interactions of feeling, confirmation,

rejection, reinforcement, and other transmissions of value within the node.

God is at every point in the node, and God is omnipresent within the social

system. Therefore God has a unique opportunity to mediate alternative values

to me, even stuck as I am in my physical location. God is an outlet for every

point in the node, a window onto a world of possibilities. It does not make

the situation in my society any less real if I am aware of other

contingencies. Instead, it simply means that this particular reality is not a

prison. It is not necessary, permanent, essential, or absolute. Nevertheless,

there can be beauty, complexity, and truth to be found in this particular

reality; there is meaning, there is value; this particular reality matters. I

need not deny the reality of my context and escape to a context-less reality,

as if such a thing could exist, in order to touch the depths of The Real. Theology is rightly concerned with meaning and value. We

as theologians seek to ground our claims for meaning and value in some

stable, justifiable location to which we can all appeal. Unlike other

disciplines in the humanities, that stable, justifiable location still tends

to get pushed out of our world. It tends to require us to venture into the

realm of the eternal and transcendent. But if theology makes that move in

search of stability, justification, and objective access, it sacrifices its

ability to reflect meaningfully on the reality of contingent particulars.

There are rich, deep, and undeniable meanings and values that cannot be extricated

from the web of contingency in which we dwell. A theology that bases itself on Whitehead’s discovery of a

system of contingency, a metaphysics of contingency, will be able to find

meaning without generalizing beyond our warrants. From the opposite perspective,

it will be able to describe and assess value in contingent sites without an

appeal to a privileged and singular source of value, an appeal that threatens

to relativize and trivialize the contingency we are actually trying to

assess. A metaphysics of contingency, based on Whitehead’s description of

distributed reality, can account for the power of communities, institutions,

all kinds of social nodes to mediate and channel values down to individuals.

Most importantly, it will provide a framework for a new theology of

contingency – a theology of immanence, adequate to concrete experience,

particular experience, deeply contingent and real experience. Such a theology

releases me from the prison of my own contingencies, but is grounded in and

reflects the ultimacy of contingency itself. Theology’s task in the

twenty-first century is to discover the depths of this new world. Notes 1 Bernard Saladin d’Anglure, "Le 'troisieme'

sexe," La Recherche 23:245

(1992). 2 Paul Tillich, Theology

of Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964). 3 4 A lecture by my colleague Richard Scott helped

shape this set of ideas. 5 See for example: Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (New York:

Fountain Press, 1929); Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women

Artists?,” Women, Art, Power, and Other

Essays (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1988), pp. 147-158; Elizabeth V.

Spelman, “Woman As Body: Ancient and Contemporary Views,” Feminist Studies 8 (1982): 109-131. 6 PR 210. 7 PR 34. 8 I am indebted to Phil Frana of the Charles

Babbage Institute at the 9 Paul Baran, “On Distributed Communications,” Rand

Corporation Memorandum RM-3420-PR. |