|

Scientific

Phrenology: Being a practical mental science and guide to human character: an illustrated text-book. By Bernard Hollander ( Taken from John van Wyhe’s

site: The History of Phrenology on the Web

http://pages.britishlibrary.net/phrenology/ CHAPTER I: WHAT IS THE USE OF A BRAIN? ALL mental operations

take place in and through the superficial grey matter, or "cortex,"

of the brain. Organic life, nutrition, circulation, excretion, secretion,

motion, in fact all vital functions can be carried on without the cortex of

the brain ; but the manifestation of the intellectual and moral powers, the

affections, and propensities or instincts of self-preservation, cannot take

place without it. Provided that the cortex of the brain be

not affected, all the other portions of the system may be diseased, or

separately destroyed, even the spinal cord may become affected, without the

mental functions being impaired. Of course if the heart, the medulla

oblongata, or some other vital part be injured, death will precede any such

experiment. If, on the other hand, the superficial grey matter of the brain

becomes compressed, irritated, injured, or destroyed, the mental functions

get partially or totally deranged or become wholly extinct. When the

compression of the brain is removed, as in the case of an indented skull, or

a tumour, or the extravasated blood or accumulated pus is evacuated, or the

cerebral inflammation allayed, consciousness and the power of thought and

feeling return. We think and feel,

rejoice and weep, love and hate, hope and fear, plan and destroy, trust and

suspect, all through the agency of the brain-cortex. Its cells record all the

events, of whatever nature, which transpire within the sphere of existence of

the individual, not merely as concerns the intellectual knowledge acquired,

but likewise the emotions passed through, and the passions indulged in. We

can only manifest our intellectual aptitudes, moral dispositions, and

tendencies to self-preservation, through the mechanism of brain with which we

happen to be endowed, and according to the sort of experience we have

accumulated. Hence though the primitive mental powers and fundamental

anatomical parts of the brain of all men are the same, we all vary according

to the mental predispositions and brain-types we have inherited and the early

education we received. The cerebral mechanism is, by dint of its original

structure, apt or otherwise for certain pursuits, moral and animal

tendencies, hence our actions are the result of the inherited organic

constitution, past education and experiences, and the circumstances which

surround us. Grapes will not grow on the thistle, but we can improve or

debase the organisation we inherited. There is in every one of us an

individuality which we are conscious is not due to training or to circumstances,

and which, however these may modify it, cannot be entirely eradicated.

Originality is kept down by transmitted tendencies, which give colour to all

our deductions from experience, and, as it were, framed us in the pursuit of

knowledge and manifestation of character. We do not all see things alike, nor

does nature awaken in all similar tastes and sympathies. Not only is it true

that certain persons distinguish themselves at a very early age by

extraordinary attainments, but certain manifestations of good or bad temper,

and other feelings, occur in very early life, before any adequate cause is

apparent. The underlying impulses \which shape man's character have in great

measure come to him as inheritances of parental virtues or vices, and they

are the capital with which he and circumstances have to work, and which, in

spite of both, must always impart colour to his every act. Parents, therefore, who

indulge chronically in evil tendencies incur great

responsibility. It is not the idea that is inherited, for there are no innate

ideas, but the disposition. During the process of making new records,

that is during the individual life of the brain, its organic memories and

inherited habits get revived, and these modify the manner of the new

recording. Though the brain may be

represented as a unit yet it contains innumerable centres with afferent and

efferent fibres, and fibres which connect them all together, a network of

intricate organic paths, along which a stimulus started may travel in

countless, but not indefinite, directions. These centres represent

organically every minute detail of knowledge and experience, they register

every definite observation and thought, and every process of reasoning with

which the individual has at any time made himself familiar

; they represent every sentiment and emotion, every affection and

passion, and indeed every one of those mental processes which are needful for

the display of what constitutes human character. All the fundamental kinds of

psychical activity are carried on in more or less distinct parts of the

cerebral hemispheres. There is the same order in the organisation of the

cerebrum as in every other organ, the same physiological division of labour,

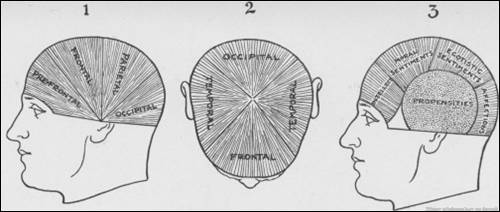

in which all organisation consists. See Plate i for

a diagrammatic representation of the direct brain-fibres, radiating from the

centre to the circumference.

The brain is more complicated,

and the convolutions more distinct and numerous, as we ascend the scale of

the animal kingdom. The essential differences obtaining in the encephalic

structure correspond to decided differences in its functions, and the

complexity of the structure is proportionate to the number of aptitudes and

propensities displayed. What can be the purpose of the difference in the

organisation of the brain in different animals, unless it be

the difference prevailing in relation to the variety of their instincts. If

it be admitted that their instincts are hereditary, then it must also be

admitted that they are due to some peculiarity in the brain-structure. One

species of animals is endowed with mental powers, in which another is

deficient, a fact that would be inexplicable, did not each particular

cerebral function reside in a particular portion of the brain. Suppose I

should enquire of my readers how it happens that certain species of animals

are devoid of the sense of smell, or some other sense, whilst they are in

full enjoyment of the rest. They would find no difficulty in such a

phenomenon. The functions of each sense, I should be told, require a

particular apparatus, and certain species may not possess one or the other of

them. But, if they admitted only one organ, through which all the senses

executed their functions, the absence of one or more in any animal would be

inexplicable. Now let the like reasoning be applied to the primitive mental

powers, the manifestation of which depends on the brain. There is scarcely

any species of animal which does not enjoy certain aptitudes and propensities

not to be found in other species. The unwieldy beaver and the nimble squirrel

are both admirable architects ; the dog, the docile,

intelligent and unwearied companion of man, has no skill in building. The

horse and bull have not the bloodthirsty propensities of the weasel and the

falcon. The sparrow and the turtle-dove do not utter the sweet notes of the

nightingale. Sheep live in flocks and rooks form communities

; the fox, the eagle, and the magpie, dislike the confinement imposed

on them by the care of their young, to which they impatiently submit during

some weeks only. The swallow, stork, fox, etc., are faithful in their

attachment to a single mate ; the dog, so susceptible

of affection, the stallion, and the stag, gratify their desires with the

first female of their species which they meet. Thus natural history, from

beginning to end, exhibits in each species of animals

different propensities and aptitudes. Does not, then, the conclusion

necessarily follow that the distinctive propensities and aptitudes of these

animals are relative to different cerebral parts ?

Were the brain the single and universal organ of them all, each animal ought

to possess them all indiscriminately. Or if the brain, as some suppose,

subserved to the intellect alone, it would be no longer possible to conceive

that man is elevated by superior intellectual faculties above all other

animals, to a far greater extent than the mere size and weight of the entire

brain would warrant. But, if it be supposed that each primitive mental power,

like each particular sense, depends on a special cerebral part, it is not

only conceivable that any one animal may be destitute of a certain cerebral

part possessed by another, but likewise that all animals generally may be

lacking in certain encephalic parts with which man is solely endowed. The intellect, moral

sentiments, affections, and propensities are so essentially different, that

there must be separate centres for them. No one supposes for an instant that

the same bundle of nerve-cells and fibres which is employed in intellectual

effort is that also through which the emotion of anger gets manifested. The mental powers

prevailing in every individual of the same species exist in very different degrees ; a circumstance only to be explained by the

different development of the several parts through which these powers are

manifested. The mastiff, bulldog, pug-dog, grey-hound, etc., are

distinguishable from each other, not by their shape only, but also by their

individual character, though they all have the character pertaining to dogs

generally. Individuals of the same variety likewise differ much from each

other, which would be impossible were each primitive quality not dependent on

a particular centre. Men possessing first-rate talents of a certain order are

sometimes perfectly insignificant in every other respect. Genius is in

well-nigh every instance partial, and limited to the exaltation of a few

mental powers, which could not be the case were the organ of mind single.

Moreover, genius not unfrequently appears at so early an age as to put study

or training, as a producing cause, entirely out of the question. No one will

deny that it is a natural gift. Have you not noticed that prodigies are quite

as childish as other children in everything but the talent by which they are

particularly distinguished. In partial idiocy the

individual is exceedingly deficient in most of the intellectual powers, and

frequently in some of the moral sentiments, and yet may possess a few of them

in considerable vigour. Thus an idiot may have a talent for imitation, for

drawing, or for music, and be incapable of comprehending a single abstract idea ; or he may show a hoarding inclination, a destructive

tendency, or the sexual instinct, and yet manifest no other power to any

perceptible extent. Were the brain a single

organ, then the innate dispositions of each man would be similar. But if the

main and accessory convolutions of the brain be appropriated to different

mental powers, then does every modification of character depend on a

different degree of development attained by these particular parts of the

brain, and their varying degree of activity. There are no

two skulls, nor two brains alike in their configuration, nor are the

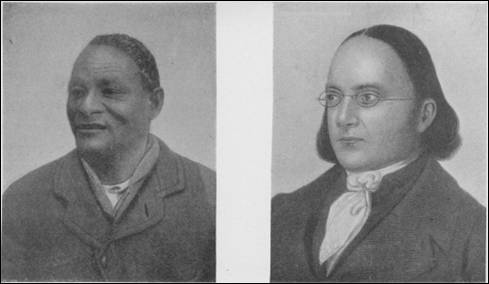

characters of any two individuals found exactly to correspond. Look at Plate

2 and compare the narrow top-head of the rebel-chief Galishwe with the broad

upper region of Dr Earth, the missionary. There is a natural

inequality in men. No two are alike in character. There prevails among

individuals an infinite variety of intellectual endowment, of moral

sentiment, affections, and instincts of self-preservation. The force and

order of the impulses differ in every one. Some young folk, though lacking in

intelligence, possess an astonishing faculty for learning by heart ; others again remarkable for their intelligence

have great difficulty in committing to memory. So with grown-up men. One will

remember dates, another localities, a third

individuals, and a fourth events. One lacks wit and gets angry at all mirth

and fun, another is deficient in dignity, another

There is a natural

inequality in men. No two are alike in character. There prevails among

individuals an infinite variety of intellectual endowment, of moral

sentiment, affections, and instincts of self-preservation. The force and

order of the impulses differ in every one. Some young folk, though lacking in

intelligence, possess an astonishing faculty for learning by heart ; others again remarkable for their intelligence

have great difficulty in committing to memory. So with grown-up men. One will

remember dates, another localities, a third

individuals, and a fourth events. One lacks wit and gets angry at all mirth

and fun, another is deficient in dignity, another dislikes children. One

expects to find the enjoyment of life in wealth, another in power, a third in

rank, a fourth in fame, while not a few are found to seek it in a mere round

of excitement. Some folk are noted for their cruelty, others for their

courage, others again for their slyness. Then there

are persons who never had any friends and do not want any. Again, a little

observation shows us that some men, apart from all training, have a decided

capacity for certain pursuits. One man excels in history, another in

geography, a third in mathematics. Some become great musicians, others

eminent painters, others distinguished poets, or actors. Most of us are

wholly devoid in some mental power : some are

baffled by arithmetic, some have no skill for drawing, some are a dead-weight

at music. Such mental quality is vouchsafed to one and denied to another. Each

has a predilection, or a more decided talent, for a particular pursuit. There

is, then, in every man something which he does not derive from education, and

which even resists all training. We follow the line of least resistance, that

is to say, the line along which our most active dispositions and abilities

drive us. From his very childhood does a man show the character which will

distinguish him in adult years. He is haughty or

humble, prudent or careless, affectionate or cold, harsh or kindly, because

it is in his nature to be so ; in other words,

because his brain organisation is so constituted. Every physician should be

able to point out these innate capacities and dispositions, and be capable of

planning for instructors rules for each pupil, in order to perfect the good

qualities and correct the evil ones, and to put the youth in a state to

employ his powers in a manner useful to himself and society at large. Seeing

the vast difference there is in the shape of heads, it is surprising that it

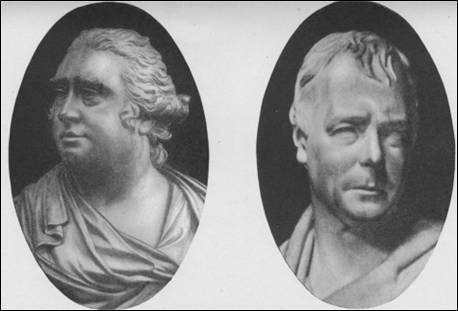

has hitherto received so little attention. Compare, for instance, the

portraits of Fox and Scott, Plate 3. Education will act on the

pupil in proportion to his innate mental powers, it will sharpen his existing

aptitudes and dispositions, but it will not supply any new one

; it cannot transform a Some of man's primary

mental powers take higher range, and some lower, but all are useful and

necessary in their proper place. Happiness signifies a gratified state of

them all. The gratification of a mental power is achieved by its exercise. To

be agreeable, that exercise must be proportionate to the development of the

aptitude or disposition ; if it be insufficient,

discontent arises, and its excess produces weariness. As long as a particular

brain-centre contains an abundance of stored up nerve force, it responds

pleasurably to a stimulus ; if the natural appetite or disposition be too

freely exercised, the nerve energy that keeps it active is used up and it ceases

to respond. This is what the voluptuary discovers to his cost. Hence, to

achieve complete felicity is to have all the mental powers exercised in the

ratio of their respective development.

It is a law of our nature

that when a thing has been done once, it is more easily achieved a second

time, and with each repetition becomes ever more easy, till at length it

grows to be natural and there is an appetite or a craving for it. The force

of early habits is such that they generally determine our practice through

life, and when once built up and strengthened are seldom if ever to be

broken. Hence the necessity for constantly guarding against evil habits and

against the practice of indulging the animal nature as opposed to the moral

and spiritual ; even the first beginning should be guarded against, the one

first act that renders the repetition thereof more easy. The aim and purpose

of the teacher then should be to render easy the doing of right and the doing

of wrong difficult, and by want of practice

unnatural and impossible. Whatever makes a good or bad action familiar to the

mind renders its performance by so much the easier. Exercise of mind implies

exercise of brain. When any part is exercised, an afflux of blood takes place

towards it, attended with heat and increased action ;

and if this be carried too far, or be persisted in too long, morbid excitement

will take the place of healthy, and derangement of function will

follow. A morbid state of any brain centre may be induced either by causes

acting directly upon its function or by causes immediately affecting the

substance of which the centre is composed. The existence of such

evidence, as I have adduced in my book on " The Mental Functions of the

Brain," to the effect that injury to the head affects one or more of the

mental powers, according to the locality on which it was inflicted, while in

other respects the individual remains perfectly sound, can only be explained

on the principle that the several portions of the cerebral hemispheres have

different functions allotted to them. So unregardful have physicians been of

this fact that many of them deemed it quite unnecessary to state in their

clinical reports in which region of the skull the injury was inflicted. But

from the number of cases accurately observed and recorded, it is evident that

injury to the brain beneath the parietal eminence, the angular and

supra-marginal convolutions, leads to Melancholia in different degrees ; that

injury at the base of the temporal bone, the middle part of the inferior

temporal convolution, leads to a manifestation of irascibility, which may end

in Violent Mania, and so on ; and that when the effects of the injury are

removed in such wise as by lifting up an indented bone, the patient recovers

his mental equilibrium. From other cases it becomes apparent that after

injury in one particular region the " sense of

relation of tones," one of the factors of the " musical

faculty," may be lost, while in another region the memory of figures and

power of calculation may disappear, leaving the other intellectual powers

normal. These facts have not hitherto been observed sufficiently, but when

they come to be so the localisation of mental functions will make rapid

advance. Similarly it has been

observed that irritation of the frontal cells is characterised by an

acceleration of the intellectual processes of perception, association, and

reproduction, giving rise to a rapid flow of ideas; and that softening of the

same part leads to dementia, whereas irritation of the parietal, occipital

and temporal area affects chiefly the emotions and propensities, often

leaving the intellect quite unclouded. That emotional display which is seen

after injury or disease of the frontal lobe is merely the weakening of the

intellectual control, which leaves the predominant bias of the individual

free to exercise itself. In certain forms of poisoning, too, such as by

Alcohol, the highest mental powers are paralysed first, thereby depriving a

man of the controlling power over his natural tendencies. Hence some

intoxicated men get dejected, others gay ; some talk

foolishly, others are eloquent ; some become effusively benevolent, others

furiously maniacal, and so on. All these facts point to there being a

congeries of centres in the cortex of the brain, not merely for the purely

intellectual operations, but also for the emotions and propensities. Experiments made on the

inferior animals by means of electricity can throw no light on the mental functions

of the brain. It is only possible to observe those functions which come under

the direct observation of the senses, symptoms which are motor in character,

and which cannot be traced back to any volitional act of the subject. But if

each portion of the nervous system governing movement be an independent local

centre of power, it is a fair inference that each portion of the nervous

system governing the mental acts is likewise an independent centre of power. In favour of there being

distinct centres in the brain is furthermore the fact of its arterial supply.

The frontal lobes are fed by the internal carotid arteries, the parietal and

occipital lobes by the basilar artery, the union of the two vertebral

arteries. The inosculation in the Circle of Willis I believe to have been

overrated. The vaso-motor nerves of these two areas are also differently

derived. Those of the posterior area spring from the inferior cervical

ganglion, into which run the fibres ascending from the abdomen, by the

greater splanchnic nerve. On the other hand the carotid arteries derive their

vaso-motor supply from the middle and superior cervical ganglia. Last, but not least, we

have the observations of numerous investigators showing that certain regions

of the cerebrum are distinguished from other regions by broad differences in

structure. Not only does the structure in different convolutions assume to a

greater or less extent a variety of modifications, but even different parts

of the same convolution may vary with regard either to the arrangement or the

relative size of their cells. These structural differences must be correlated

with some difference of function. The group of cells whose function is purely

intellectual cannot possibly have the same construction as a group of cells

whose function is purely emotional. The two may be united by association

fibres, so that one may rouse the other, but the function of each group of

cells must be distinct. Though we may speak of a

centre, it is understood that as there are two hemispheres of the brain,

every centre is two-fold, and to this fact may be due those few instances in

which a particular centre got injured or destroyed without a loss of any

mental power being discoverable. This is especially the case in accidents to

the right half of the brain, which seems to be less active than the left.

Where the two halves are unequal, I have frequently observed that the right

represents what the individual is by nature, i.e. his inherited organisation, and the left what he has made of it. The more highly developed

the mental powers, the more connected will the various centres of the brain

become by means of intricate channels of the freest intercommunication.

Though the centres themselves are distinct, all of them are interunited, and

the activity of each depends on its relation to the others. It is therefore a

mistake to look for a protuberance of brain-matter, or a bump on its

outer-covering, the skull. No one centre is competent to manifest itself by

itself. Each acts as a portion of the brain to modify the general result of

cerebral action. It is through this solidarity and interdependence that no

portion of it can be injured or exhausted without its interfering in some way

with the functions of the other portions. There is, however, a great

difference between saying that the various brain-parts exert a mutual

influence, and saying that each part does not perform its own particular

function. The positions of the centres are not accidental, but are governed

by fixed principles. One centre fuses with another,

hence neighbouring centres are related in their mental manifestation. Centres

are of a higher character, and of later acquisition, in proportion as they

occupy a higher locality in the brain. Thus the highest mental powers will be

found farthest from the base of the brain, for the rigid base of the skull

does not admit of much extension. On the other hand, the vault of the skull

remains open in two places at least for some time after birth, and even in

later life is still capable of an increased arching to make room for

increased brain-mass. The lowest and most indispensable mental powers-for

instance, the instincts of self-preservation common to men and animals-will

be found at the base of the brain ; the highest mental powers, and of later

acquisition- for instance, the moral sentiments-are at the top of the head,

in the superior part of the frontal convolutions. |