The

Teleological Argument

By

William Paley Excerpts

from Natural Theology (1800) Chapter

1: “State of the Argument”

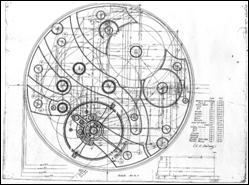

In

crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone and were

asked how the stone came to be there, I might possibly answer that for

anything I knew to the contrary it had lain there forever; nor would it,

perhaps, be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had

found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch

happened to be in that place, I should hardly think of the answer which I had

before given, that for anything I knew the watch might have always been

there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the

stone? Why is it not as admissible in the second case as in the first? For

this reason, and for no other, namely, that when we come to inspect the

watch, we perceive -- what we could not discover in the stone -- that its

several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g., that they are

so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as

to point out the hour of the day; that if the different parts had been

differently shaped from what they are, of a different size from what they

are, or placed after any other manner or in any other order than that in

which they are placed, either no motion at all would have been carried on in

the machine, or none which would have answered the use that is now served by

it. To reckon up a few of the plainest of these parts and of their offices,

all tending to one result; we see a cylindrical box containing a coiled

elastic spring, which, by its endeavor to relax itself, turns round the box.

We next observe a flexible chain -- artificially wrought for the sake of

flexure -- communicating the action of the spring from the box to the fusee.

We then find a series of wheels, the teeth of which catch in and apply to

each other, I. Nor

would it, I apprehend, weaken the conclusion, that we had never seen a watch

made -- that we had never known an artist capable of making one -- that we

were altogether incapable of executing such a piece of workmanship ourselves,

or of understanding in what manner it was performed; all this being no more

than what is true of some exquisite remains of ancient art, of some lost

arts, and, to the generality of mankind, of the more curious productions of

modern manufacture. Does one man in a million know how oval frames are

turned? Ignorance of this kind exalts our opinion of the unseen and unknown

artist's skiff, if he be unseen and unknown, but raises no doubt in our minds

of the existence and agency of such an artist, at some former time and in

some place or other. Nor can I perceive that it varies at all the inference,

whether the question arise concerning a human agent or concerning an agent of

a different species, or an agent possessing in some respects a different

nature. II. Neither, secondly, would it invalidate our conclusion,

that the watch sometimes went wrong or that it seldom went exactly right. The

purpose of the machinery, the design, and the designer might be evident, and

in the case supposed, would be evident, in whatever way we accounted for the

irregularity of the movement, or whether we could account for it or not. It

is not necessary that a machine be perfect in order to show with what design

it was made: still less necessary, where the only question is whether it were

made with any de- sign at all. III. Nor, thirdly, would it bring any uncertainty into the

argument, if there were a few parts of the watch,, concerning which we could

not discover or had not yet discovered in what manner they conduced to the

general effect; or even some parts, concerning which we could not ascertain

whether they conduced to that effect in any manner whatever. For, as to the first

branch of the case, if by the loss, or disorder, or decay of the parts in

question, the movement of the watch were found in fact to be stopped, or

disturbed, or retarded, no doubt would remain in our minds as to the utility

or intention of these parts, although we should be unable to investigate the

manner according to which, or the connection by which, the ultimate effect

depended upon their action or assistance; and the more complex is the

machine, the more likely is this obscurity to arise. Then, as to the second

thing supposed, namely, that there were parts which might be spared without

prejudice to the movement of the watch, and that we had proved this by

experiment, these superfluous parts, even if we were completely assured that

they were such, would not vacate the reasoning which we had instituted concerning

other parts. The indication of contrivance remained, with respect to them,

nearly as it was before. IV. Nor, fourthly, would any man in his senses think the

existence of the watch with its various machinery accounted for, by being

told that it was one out of possible combinations of material forms; that

whatever he had found in the place where he found the watch, must have

contained some internal configuration or other; and that this configuration

might be the structure now exhibited, namely, of the works of a watch, as

well as a different structure. V. Nor, fifthly, would it yield his inquiry more

satisfaction, to be answered that there existed in things a principle of

order, which had disposed the parts of the watch into their present form and

situation. He never knew a watch made by the principle of order; nor can he

even form to himself an idea of what is meant by a principle of order

distinct from the intelligence of the watchmaker. VI. Sixthly, he would be surprised to hear that the mechanism

of the watch was no proof of contrivance, only a motive to induce the mind to

think so: VII. And not less surprised to be informed that the watch in

his hand was nothing more than the result of the laws of metallic

nature. It is a perversion of language to assign any law as the efficient,

operative cause of any thing. A law presupposes an agent, for it is only the

mode according to which an agent proceeds: it implies a power, for it is the

order according to which that power acts. Without this agent, without this

power, which are both distinct from itself, the law does nothing, is

nothing. The expression, "the law of metallic nature," may sound

strange and harsh to a philosophic ear; but it seems quite as justifiable as

some others which are more familiar to him, such as "the law of

vegetable nature," "the law of animal nature," or, indeed, as

"the law of nature" in general, when assigned as the cause of

phenomena, in exclusion of agency and power, or when it is substituted into

the place of these. VIII. Neither, lastly, would our observer be driven out of his

conclusion or from his confidence in its truth by being told that he knew

nothing at all about the matter. He knows enough for his argument; he knows

the utility of the end; he knows the subserviency and adaptation of the means

to the end. These points being known, his ignorance of other points, his

doubts concerning other points affect not the certainty of his reasoning. The

consciousness of knowing little need not beget a distrust of that which he

does know. Chapter

2: “State of the Argument Continued”

Suppose,

in the next place, that the person who found the watch should after some time

discover that, in addition to all the properties which he had hitherto

observed in it, it possessed the unexpected property of producing in the

course of its movement another watch like itself -- the thing is conceivable;

that it contained within it a mechanism, a system of parts -- a mold, for

instance, or a complex adjustment of lathes, baffles, and other tools --

evidently and separately calculated for this purpose; let us inquire what

effect ought such a discovery to have upon his former conclusion. I. The first effect would be to increase his admiration of

the contrivance, and his conviction of the consummate skill of the contriver.

Whether he regarded the object of the contrivance, the distinct apparatus,

the intricate, yet in many parts intelligible mechanism by which it was

carried on, he would perceive in this new observation nothing but an

additional reason for doing what he had already done -- for referring the

construction of the watch to design and to supreme art. If that construction without

this property, or, which is the same thing, before this property had been

noticed, proved intention and art to have been employed about it, still more strong

would the proof appear when he came to the knowledge of this further

property, the crown and perfection of all the rest. II. He would reflect, that though the watch before him were, in

some sense, the maker of the watch, which, was fabricated in the course

of its movements, yet it was in a very different sense from that in which a

carpenter, for instance, is the maker of a chair -- the author of its

contrivance, the cause of the relation of its parts to their use. With

respect to these, the first watch was no cause at all to the second; in no

such sense as this was it the author of the constitution and order, either of

the arts which the new watch contained, or of the parts by the aid and

instrumentality of which it was produced. We might possibly say, but with

great latitude of expression, that a stream of water ground corn; but no

latitude of expression would allow us to say, no stretch of conjecture could

lead us to think that the stream of water built the mill, though it were too

ancient for us to know who the builder was. What the stream of water does in

the affair is neither more nor less than this: by the application of an

unintelligent impulse to a mechanism previously arranged, arranged

independently of it and arranged by intelligence, an effect is produced,

namely, the corn is ground. But the effect results from the arrangement. The

force of the stream cannot be said to be the cause or author of the effect,

still less of the arrangement. Understanding and plan in the formation of the

mill were not the less necessary for any share which the water has in

grinding the corn; yet is this share the same as that which the watch would

have contributed to the production of the new watch, upon the supposition

assumed in the last section. Therefore, III. Though it be now no longer probable that the individual

watch which our observer had found was made immediately by the hand of an

artificer, yet does not this alteration in anyway affect the inference that

an artificer had been originally employed and concerned in the production.

The argument from design remains as it was. Marks of design and contrivance

are no more accounted for now than they were before. In the same thing, we

may ask for the cause of different properties. We may ask for the cause of

the color of a body, of its hardness, of its heat; and these causes may be

all different. We are now asking for the cause of that subserviency to a use,

that relation to an end, which we have remarked in the watch before us. No

answer is given to this question by telling us that a preceding watch

produced it. There cannot be design without a designer; contrivance without a

contriver; order without choice; arrangement without anything capable of

arranging; subserviency and relation to a purpose without that which could

intend a purpose; means suitable to an end, and executing their office in

accomplishing that end, without the end ever having been contemplated or the

means accommodated to it. Arrangement, disposition of parts, subserviency of

means to an end, relation of instruments to a use imply the presence of

intelligence and mind. No one, therefore, can rationally believe that the

insensible, inanimate watch, from which the watch before us issued, was the

proper cause of the mechanism we so much admire in it -- could be truly said

to have constructed the instrument, disposed its parts, assigned their

office, determined their order, action, and mutual dependency, combined their

several motions into one result, and that also a result connected with the utilities

of other beings. All these properties, therefore, are as much unaccounted for

as they were before.

The

question is not simply, How came the first watch into existence? which

question, it may be pretended, is done away by supposing the series of

watches thus produced from one another to have been infinite, and

consequently to have had no such first for which it was necessary to

provide a cause. This, perhaps, would have been nearly the state of the

question, if nothing had been before us but an unorganized, unmechanized

substance, without mark or indication of contrivance. It might be difficult

to show that such substance could not have existed from eternity, either in

succession -- if it were possible, which I think it is not, for unorganized

bodies to spring from one another -- or by individual perpetuity. But that is

not the question now. To suppose it to be so is to suppose that it made no

difference whether he had found a watch or a stone. As it is, the metaphysics

of that question have no place; for, in the watch which we are examining are

seen contrivance, design, an end, a purpose, means for the end, adaptation to

the purpose. And the question which irresistibly presses upon our thoughts

is, whence this contrivance and design? The thing required is the intending

mind, the adapting hand, the intelligence by which that hand was directed.

This question, this demand is not shaken off by increasing a number or

succession of substances destitute of these properties; nor the more, by

increasing that number to infinity. If it be said that, upon the supposition

of one watch being produced from another in the course of that other's

movements and by means of the mechanism within it, we have a cause for the

watch in my hand, namely, the watch from which it proceeded; I deny that for

the design, the contrivance, the suitableness of means to an end, the

adaptation of instruments to a use, all of which we discover in the watch, we

have any cause whatever. It is in vain, therefore, to assign a series of such

causes or to allege that a series may be carried back to infinity; for I do

not admit that we have yet any cause at all for the phenomena, still less any

series of causes either finite or infinite. Here is contrivance but no

contriver; proofs of de- sign, but no designer. The

conclusion which the first examination of the watch, of its works,

construction, and movement, suggested, was that it must have had, for cause

and author of that construction, an artificer who understood its mechanism

and designed its use. This conclusion is invincible. A second

examination presents us with a new discovery. The watch is found, in the

course of its movement, to produce another watch similar to itself; and not

only so, but we perceive in it a system of organization separately calculated

for that purpose. What effect would this discovery have or ought it to have

upon our former inference? What, as has already been said, but to increase

beyond measure our admiration of the skill which had been employed in the

formation of such a machine? Or shall it, instead of this, all at once turn

us round to an opposite conclusion, namely, that no art or skill whatever has

been concerned in the business, although all other evidences of art and skill

remain as they were, and this last and supreme piece of art be now added to

the rest? Can this be maintained without absurdity? Yet this is atheism. . .

. Chapter

5: “Application of the Argument Continued”

Every

observation which was made in our first chapter concerning the watch may be

repeated with strict propriety concerning the eye, concerning animals,

concerning plants, concerning, indeed, all the organized parts of the works

of nature. As, I. When we are inquiring simply after the existence

of an intelligent Creator, imperfection, inaccuracy, liability to disorder,

occasional irregularities may subsist in a considerable degree without

inducing any doubt into the question; just as a watch may frequently go

wrong, seldom perhaps exactly right, may be faulty in some parts, defective

in some, without the smallest ground of suspicion from thence arising that it

was not a watch, not made, or not made for the purpose ascribed to it. When

faults are pointed out, and when a question is started concerning the skill

of the artist or dexterity with which the work is executed, then, indeed, in

order to defend these qualities from accusation, we must be able either to

expose some intractableness and imperfection in the materials or point out

some invincible difficulty in the execution, into which imperfection and

difficulty the matter of complaint may be resolved; or, if we cannot do this,

we must ad- duce such specimens of consummate art and contrivance proceeding

from the same hand as may convince the inquirer of the existence, in the case

before him, of impediments like those which we have mentioned, although, what

from the nature of the case is very likely to happen, they be unknown and

unperceived by him. This we must do in order to vindicate the artist's skill,

or at least the perfection of it; as we must also judge of his intention and

of the provisions employed in fulfilling that intention, not from an instance

in which they fail but from the great plurality of instances in which they

succeed. But, after all, these are different questions from the question of

the artist's existence; or, which is the same, whether the thing before us be

a work of art or not; and the questions ought always to be kept separate in

the mind. So likewise it is in the works of nature. Irregularities and

imperfections are of little or no weight in the consideration when that

consideration relates simply to the existence of a Creator. When the argument

respects His attributes, they are of weight; but are then to be taken in

conjunction-the attention is not to rest upon them, but they are to be taken

in conjunction with the unexceptionable evidence which we possess of skill,

power, and benevolence displayed in other instances; which evidences may, in

strength, number, and variety, be such and may so overpower apparent

blemishes as to induce us, upon the most reasonable ground, to believe that

these last ought to be referred to some cause, though we be ignorant of it,

other than defect of knowledge or of benevolence in the author. . . . |