Want it on paper instead? Download the .pdf document! It's printer-friendly and paper fits easily inside your lab notebook...which you may want come quiz day...

Make sure that you are recording everything you do in your lab notebook. When you take your quiz in class next week, you will be allowed to use your notebook, a calculator, and clicker, but no additional resources.

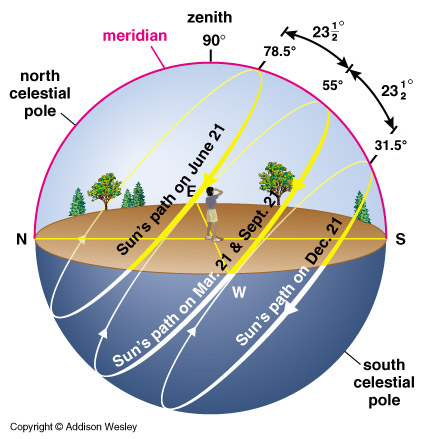

IntroductionSome of our most basic knowledge of astronomy is based on observing the sun and its position in the sky. Unfortunately, some of things we "know" are not entirely correct! One common misconception is that the sun is directly overhead at noon. Whether or not the sun is straight overhead depends on where you are on the globe, what time of year it is, and what you mean by "noon." Similarly, we all know that one day is 24 hours long. Our entire calendar is based on this fact! However, the measurement of the rotation rate of any object must be done with respect to some reference point. When we measure the time it takes for the Earth to complete one full rotation, it turns out that it makes a difference whether we measure it with respect to the sun or with respect to a distant star. Objectives

ProcedureLaunch the Stellarium program and set your location for right here in Conway, AR. Make sure you are located at the correct place on the map before you continue. If it is not already, make this your default location (so that the program will automatically place you at the correct location on startup). Noon Is 12:00, Right?Again, we all know when noon is...it's 12:00 noon. The sun is straight overhead at noon, right? Check it.

A more precise definition for solar noon is the time when the sun crosses the meridian (the imaginary line from due N to due S can be turned on from the Viewing Options window). Toggle the meridian on.

|

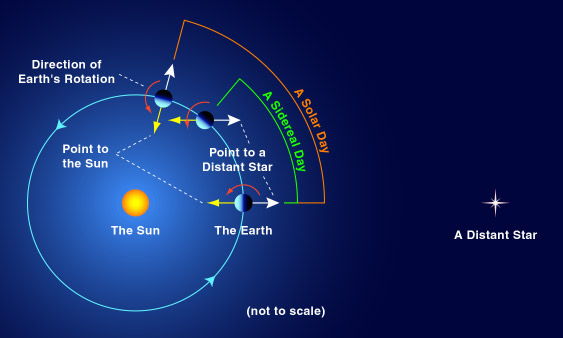

And a Day Is a Day Is a Day...A solar and sidereal day each measure the rotation of the earth, but in relation to different objects. The solar day looks at rotation with respect to the sun: how long does it take for the earth to complete one rotation with respect to the sun (noon to noon, as long as you are measuring noon with respect to the meridian). The sidereal day measures the same thing, but uses a distant star instead (any star will do).

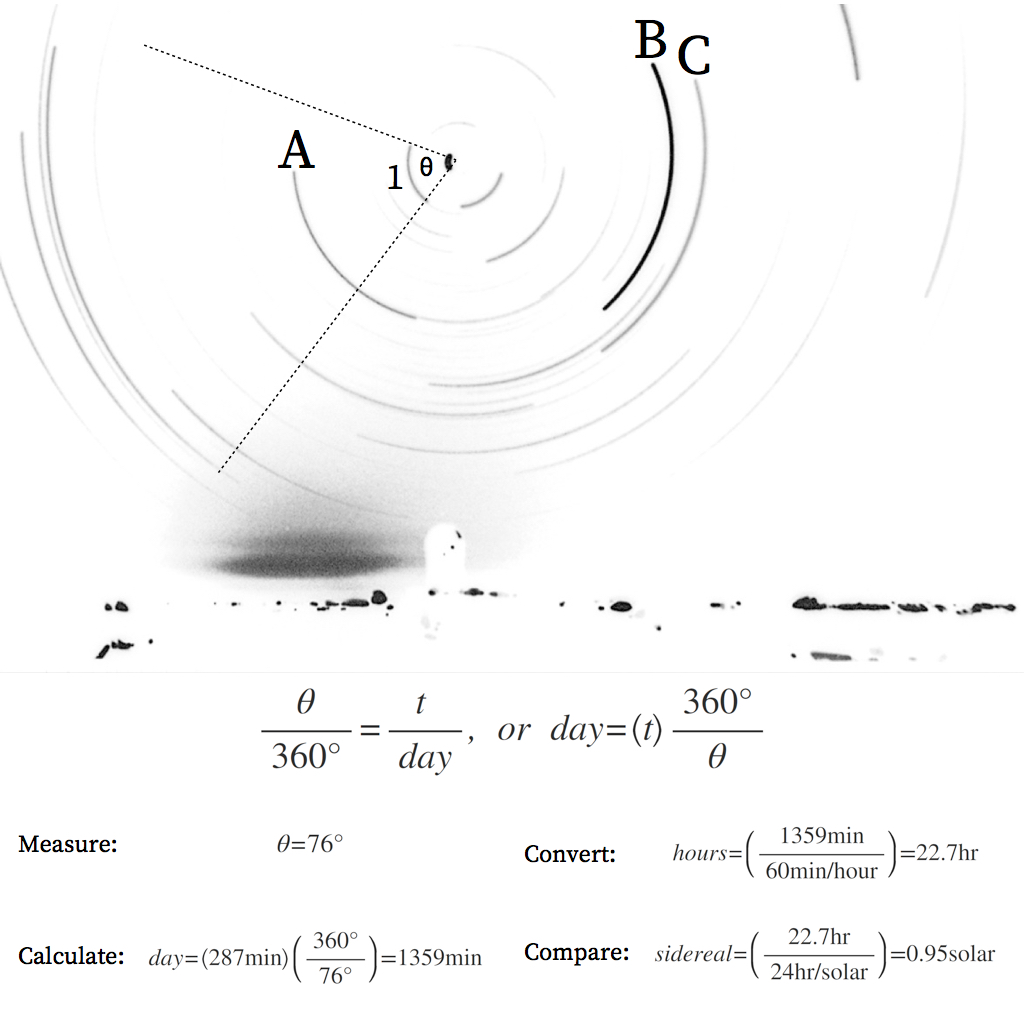

Shown below is Figure 0.5 (page 06) from the textbook. It has been color-inverted so that the sky appears white and the starlight appears gray or black. A long photographic exposure will show the apparent path of the stars as the earth spins. Thus, in exactly one sidereal day, a star would trail out a complete circle of 360°. By measuring the fraction of that circle exposed, and knowing the length of the exposure, you can experimentally calculate the length of the sidereal day.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||